by Councilman Charlie Brown

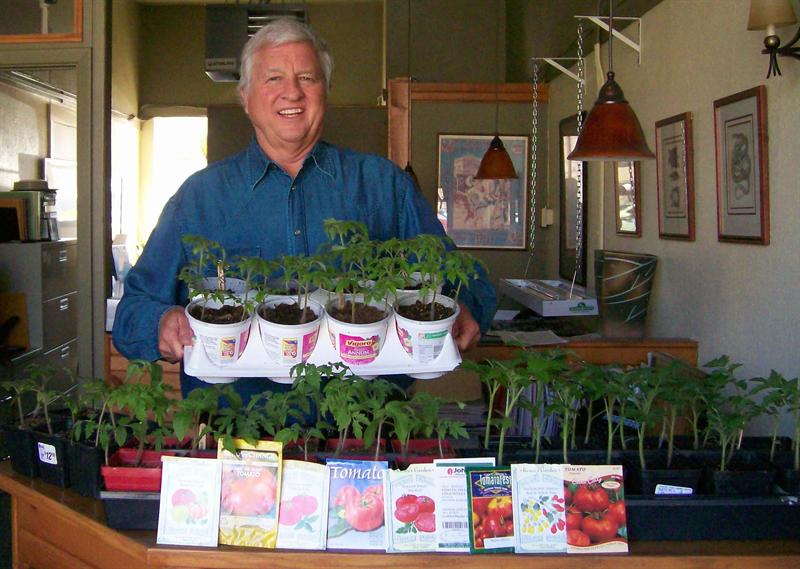

For the last eight seasons, Denver City Councilman Charlie Brown has planted thousands of tomato seeds in March and nurtured the plants to distribute free to residents and city officials in early May. He grows them in his basement and office, where they eventually end up in his office windows on Exposition Avenue and are often confused with a newly legalized plant.

“When that happens,” Brown said, “I always remind folks that tomato plants are not a cash crop.”

“When that happens,” Brown said, “I always remind folks that tomato plants are not a cash crop.”

The second year his efforts proved so popular that constituents started calling in April wanting to know when they could pick up “their” tomato plants. The “The Tomato Plant Entitlement Program” was hatched.

This year was his biggest yet, with more than 800 plants and 15 varieties handed out. And it will be the last year to do so, since along with five other Denver council members, he is term-limited in July. He has represented 52,000 residents in south Denver for more than 14 years.

Brown calculates he has distributed some 6,000 tomato plants during the last eight years which, if urban gardeners followed his tip sheet for growing in Denver’s fickle climate, produced 20,000 pounds of America’s favorite gardening crop. And with this era ending, he wanted to share how he got started — not with politics, but with gardening.

The love affair began decades ago.

My first gardening memories can be traced back to my grandparents’ small farm five miles east of Durham, N.C. When we were about 10-years-old, my Mom would take my twin brother and me there to spend the weekend helping them with farm chores.

Saturday mornings started early. A rooster’s cock-a-doodle-doo would send us dashing off to the hen house to gather fresh brown eggs for breakfast. That was the easy start of a long day working in the heat and humidity and the sandy clay soils of North Carolina’s Piedmont region. We milked cows, fed the pigs and chickens, and tackled the dreaded hoeing and weeding.

I would do things that city folks have trouble understanding, including wringing a chicken’s neck for Sunday supper and watching it run around the barnyard with no head; and plowing long rows of crops with a large, tail-swishing beast six feet in front of me who, surprisingly, respected my commands of “whoa mule!” I loved every minute of it, especially the gardening.

The southern climate allowed for early planting and harvesting. It’s hard for Denver gardeners to fathom that by late June we were already “bringing in” potatoes, broccoli, spinach, beets, onions, field peas, squash, butter beans, string beans, green peppers and, my favorite, tomatoes. Okra, turnip greens, cantaloupe, watermelon and corn would soon follow. Most crops would be “put up” in canning jars or, later, a small Sears & Roebuck freezer.

As I look back on those days I realize just how much my grandparents taught me. My grandmother was an early naturalist, who loved birds, wildlife and gardening. “Gardening teaches you patience,” she said. She reminded us not to keep all the fish we caught from the scummy farm pond but return some for ‘another day’ long before the concept of “catch and release.” My grandfather was a hard task master. If he would catch us leaning on our hoe to catch a quick break he would yell out: “You have to hoe to the end of the row,” a work ethic that’s sometimes hard for youngsters to comprehend.

Thanks to the influence of my grandparents, I’ve planted a garden each spring for more than 40 years. It gets in your blood. When it hails in Denver everyone is concerned about their cars and roofs. But like all farmers, ranchers and urban gardeners, our concern is about, in the words of Kenny Rogers, “our crops in the field.”