Written by Luke Schmaltz

The sweltering months of 2019 were bumper-to-bumper trouble for U.S. Highway 36 commuters.

If you are one of the 107,000 motorists or public transportation customers who traverse this corridor daily, here’s hoping your vehicle has air conditioning, your playlist is extensive, and your boss knows you’re going to be late.

A considerable crack in the surface layer appeared July 12, 2019, prompting Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) crews to close the eastbound lanes at Church Ranch Blvd. The decision was indeed prudent, as the fissure soon gave way to a gap that eventually ruptured into a ditch-like sinkhole in the road.

By July 15, 2019, traffic in both directions had been diverted to two respective lanes of the westbound corridor — resulting in a bottleneck effect in an already heavily congested zone. This allowed some traffic flow, however sluggish, so that CDOT crews could access the area, analyze the damage and embark on a massive repair project.

Meanwhile, the event sparked several issues, as area residents, CDOT personnel and daily commuters began to ponder the obvious. How long would it be before the damage was fixed, why had a new stretch of road caved in like the top of a half-baked cake, and perhaps most importantly, where would the money come from to pay for the reconstruction?

A Dubious Timeline

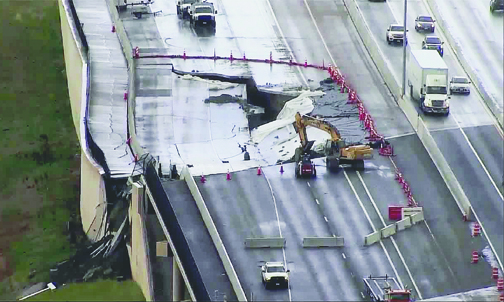

Lateral and aerial photos revealed a multi-dimensional calamity, as the horizontal depression in the road was countered by a vertical eruption of retaining wall concrete slabs, debris-ridden soil and mangled rebar. On July 15, 2019, CDOT chief engineer Josh Laipply was quoted by several news outlets including Colorado Public Radio (CPR) as stating that it would be “weeks” before the highway would be returned to an operational condition. Several days later, that statement was amended by CDOT Executive Director Shoshana Lew, who offered that it would be “a matter of months” for the repair to be completed.

Meanwhile CDOT Communications Director Matt Inzeo via phone interview declined to comment on a projected timeline. He pivoted instead and offered that the retaining wall-supported embankment upon which the highway was built sits next to a “wetlands area that used to be a lake.”

A Sinking Feeling

The aforementioned information, perhaps inadvertently, placed a certain gravity on a statement issued by CDOT spokesperson Tamara Rollison, who explained “It appears water has gotten underneath the section that’s collapsing. It looks like it’s unraveling.”

At this point in the story, the term “collapsing soils” was introduced as a possible culprit. A blog published by CPR offered a statement from professor of construction engineering management at CU Boulder, Cristina Torres-Machi. It states: “[Torres-Machi] said it looks like a nearly textbook example of what she called ‘slope failure,’ essentially a landslide … She said it’s likely because of collapsing soils.”

Just in case (like most folks) you are not a geology major, collapsing soils are comprised of dry, low-density particles which can withstand significant impact without losing volume. Once water is introduced, however, the particles break apart, densify and undergo a significant reduction in volume. Oftentimes this results in the sudden appearance of a sinkhole.

In early August, a phone interview with Colorado Geological Survey Senior Engineering Geologist Jonathan White revealed contrary information that seemed to muddy the waters. Professor White explained that the embankment supporting the highway was comprised of “highly saturated, already wet soils” and the sinkhole was “most likely caused by a lateral landslide” and “was not the result of the presence of collapsing soils.” Professor White explained further that the wetlands adjacent to the highway were inherently responsible for the preliminary presence of moisture in the soil beneath the highway. He finished by stating that sudden influx of more water did not cause a collapsing soil situation and the disaster was more likely attributable to “an engineering issue.”

Who’s Going To Pay For This?

If Professor White is indeed correct, then upon whose shoulders gets foisted the blame? If it is neither the cause of collapsing soils or the effects of plain ol’ gravity, then by default, human error takes the spotlight. Regardless, the road must be repaired. A massive reconstruction project was launched as soon as engineers determined the debris and soil had ceased to shift and collapse.

This section of highway was completed just over five years ago in a joint venture between Granite Construction of California and Ames Construction of Aurora. By all estimations, it should most certainly not be crumbling, yet until engineering failure on the behalf of the contractors is found to be the cause, other monies have been allocated to pay for the reconstruction.

With Colorado’s massive influx of marijuana-based tax revenue, it is clear the $20.4 million repair and reimbursement estimate should be easy to meet by this revenue stream alone. After all, in 2019 alone, total tax revenue is projected by the Colorado Department of Revenue to be somewhere around the $30 million mark. Some experts believe it stands to reason that coffers swelling with monetary influx that was virtually nonexistent when that section of the road was built should rightly be tapped to remedy its untimely demise. Yet, when pressed for information on where the “contingency funds” allocated by the State Transportation Commission were being siphoned from, representatives of CDOT, Colorado Department of Revenue and Colorado Department of the Treasury declined to elaborate. A representative of the latter (who refused to be named) offered only the tersely toned retort “… well, first of all, treasury is not revenue.” Whatever that is supposed to mean, it sounds about as solid as collapsing soil.