by Robert Davis

As City Council prepares to vote on the Group Living Proposal in October, several neighborhood organizations and residents are sounding off against the plan, saying it doesn’t address the right issues and would negatively impact neighborhood characteristics.

Their calls are growing so loud that it’s causing some councilmembers’ support for the proposal to waiver.

Group Living Proposal

The Group Living Proposal was developed by CPD to address rising housing costs and the threat of displacement for Denver’s low-income residents. The plan seeks to overhaul several parts of Denver’s zoning code. Most notably, the number of unrelated people that can live together in a single-family dwelling would increase to eight from its current limit of four. It would also consolidate group living use restrictions into two categories — Residential Care and Congregate Living — and allow developers to build them in single-family neighborhoods.

Residential Care include homeless shelters, community corrections facilities, and sober living homes. Dormitories and tiny home villages are examples of Congregate Living facilities.

Following the bill’s hearing before the Land Use, Transportation, and Infrastructure Committee (LUIT) on September 1, Councilwomen Amanda Sawyer (District 5) and Kendra Black (District 4) penned an op-ed in The Denver Post calling for the plan to undergo a more strenuous review before it’s approved.

“We don’t dispute the need for change. However, rubber-stamping this proposal is not the best way to update the code to modern reality,” they wrote. “With CPD now kicking off a two-year project aimed at eliminating single family zoning, and neighborhood plan updates underway across the city, we have to look at group living in a broader context.”

Councilmembers Kevin Flynn (District 2), Jolon Clark (District 7), and Paul Kashmann (District 3) co-signed the op-ed.

In the op-ed, the councilmembers objected to the fact that the plan does not address the most problematic part of the city’s zoning code, Chapter 59. It was adopted in 1956 and has functioned as Denver’s second zoning code since 2010 when the city adopted its new code. Properties covered by Chapter 59 make up approximately 20 percent of Denver’s total zone districts, according to city estimates.

City auditor Timothy O’Brien issued a report in 2015 saying the coexistence of both zoning codes negatively impacts the “equal treatment of all citizens and long-term success of the city’s goals.” CPD agreed with O’Brien’s recommendation to undertake a cost-benefit analysis of switching to a single zoning code, but it was never implemented.

Neighborhood organizations and residents have been echoing these concerns since March, according to Jerry Doerskin, a Southmoor Park resident. Doerskin says the plan lacks practicality and should affect the entire city if it’s truly worth its salt.

“It’s grossly unfair to impose these kinds of zoning changes on four-fifths of Denver and leave the rest untouched,” he told the Glendale Cherry Creek Chronicle.

Doerskin says the practical application of the plan will ruin the characteristics of his neighborhood by severely taxing the city’s aging infrastructure.

In January, Colorado’s mayors united to call for more infrastructure funding after the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) gave the state a C- on its 2020 infrastructure report card. ASCE found the state’s roads, drinking water supply, and energy grid face significant challenge because the state hasn’t adequately maintained its infrastructure, amounting to a $14 billion funding gap.

Over the past two years, state lawmakers have given $2.7 billion to cities and counties to help pave their roads. However, this creates a paradox for the state’s budget, as it is now being asked to support local road projects when it’s proven to be ineffective at adequately funding state projects.

Infrastucture was a driving force behind Doerskin and other members of a group he co-founded to oppose the Group Living Proposal called Safe and Sound Denver, submitting a petition with over 2000 signatures of Denver residents who oppose the proposal prior to the September 1 LUIT meeting.

“There is very little to support in this bill,” he said. “I know addressing homelessness and high living costs in Denver are valid concerns, but to totally increase density like this is unreasonable. I could support a moderate increase of unrelated people living together. But, if that’s not acceptable to Council, they should vote it down and take up the issues one at a time.”

High Hurdles

Even if Denver didn’t have an infrastructure issue, existing state laws present hurdles to development that lawmakers haven’t figured out how to cross.

Colorado outlawed inclusionary zoning practices in 1981, thus preventing cities and counties from implementing rent control policies and requiring developers to set aside a certain amount of units for low-income residents. In 2000, the Colorado Supreme Court reinforced the law in Telluride v. Thirty-Four Venture when it added home rule municipalities to its jurisdiction.

Denver-area Democrats have tried to pass legislation overturning the Telluride decision in 2020, but it never made it out of committee.

On top of these restrictions, Denver has a hard time incentivizing developers to build affordable units because the of the city’s construction permit fees. Developers may be asked to pay permit fees which are determined based on the value of their project and an extra fee to expedite the city’s review of their permit application. After that, developers have to pay an affordable housing fee of up to $1.65 per square foot.

Once the coronavirus pandemic hit and material prices began to skyrocket, the city faced even higher hurdles. The price of lumber has climbed $300 per thousand board-feet since mid-March and steel has increased 10 percent to almost 3700 Yuan.

A Private Enterprise

While Group Living Proposal supporters claim they are looking toward Denver’s future, some residents worry the city will be dragging along historical problems.

In 2017, CPD coordinated with the mayor’s office to create the Group Living Advisory Committee (GLAC), a 48-member congregation of community members, neighborhood organizations, private and public interests tasked to identify outdated areas of the city’s zoning code.

Members represent various industries ranging from corrections to homeless services and developers. Both At-large councilwomen, Robin Kneich and Deborah Ortega, represent City Council.

Neighborhood organizations make up just eight representatives on GLAC, leading some residents like Paige Burkeholder, to suspect that the project is meant to serve private interests and help term-limited politicians like Mayor Michael Hancock line up future campaign donations.

“Overall, this is such a massive overhaul to the zoning code with very little input and dialog from residents of neighborhoods,” Burkeholder told the Chronicle.

Two GLAC members Burkeholder focuses on are Geo Group and Core Civic, both of whom are private corrections companies. Between 2012 and 2017, both companies spent approximately $718,000 to lobby state lawmakers in Colorado, according to Follow The Money, a campaign finance research database.

Core Civic runs its state-level lobbying operations through Greenberg Taurig, a firm several councilmembers know well. Since 2003, Greenberg Taurig has donated at least $23,000 between Hancock and Ortega’s campaigns, according to each candidate’s financial disclosure forms. An overwhelming majority of the donations went to Mayor Hancock.

What About The Future?

Colorado has been experimenting with similar rules since July when Governor Polis suspended limitations on the number of people who can live together to help unhoused and displaced people into the state’s shelter system. Similarly, LUTI passed a temporary moratorium on group living developments in Chapter 59 communities and CPD issued a memo in September staff saying the agency considers enforcement of group living rules its lowest priority in September.

But, while these changes are neither permanent nor readily noticeable for many residents, some say the focus should continue to be on the future of the proposal and nailing down how it will impact homeowners across Denver.

“The only way to make this proposal work is to go back to the beginning and start over,” Burkeholder said. “We need to make sure every voice is heard, not just the one’s the city wants to hear.”

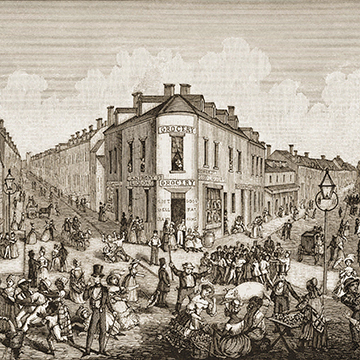

Exemplar: Drawing of Group Living in the Five Points area of New York circa 1840.