“It’s not vaccines that save lives, it’s vaccinations.”

— Stephanie Wasserman, Executive Director, Immunize Colorado

The strategy for combating the spread of Covid-19 and thus, reducing the subsequent fallout of loss and tragedy is fairly simple: inoculate the population. While this equation reads well on paper, implementing it across the Mile High region has a distinct set of challenges.

From a practical standpoint, it would seem that the biggest obstructions to vaccine distribution would be the tiered system of rollout phases (eligibility based on vulnerability) and the availability of enough doses for each demographic. While this is certainly the case, vaccine task force officials — including government appointed teams and private sector organizations — are facing formidable yet invisible hurdles anchored in misinformation and inter-generational mistrust of the medical system at large.

A Clearly Laid-Out Plan

The Office of Colorado Governor Jared Polis, in conjunction with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), have established a series of phases to be implemented in a systematic, step-by-step fashion.

Phase One begins with high-risk individuals and healthcare workers (1A), people age 70+, moderate risk healthcare workers and first responders (1B.1), citizens aged 65-69, pre-K-12 educators, cold care workers and continuity of state government officials (1B.2), people aged 16-64 with two or more comorbidities and frontline workers (1B.3).

Phase Two includes Coloradans 60-64, people with high-risk conditions and continuity of operation workers in state and local government.

Phase Three, at last, includes anyone and everyone in the general population ages 16-59.

Governor Polis has gone so far as to speculate, as stated in a recent article by The Denver Post, that he expects folks to be returning to their beloved restaurants, nightclubs and bars by May, in a gradual transition of systematically loosening restrictions and returning everyday personal freedoms.

At the time of this writing, rollout of phase 1B.2 is underway and just about everyone involved in education including teachers, substitutes, bus drivers, cafeteria workers, janitors, and other support staff will be able to access the vaccine as will select members of the executive and judicial branches of government. These folks do not present an accessibility concern for vaccinators, but the other demographic this phase accommodates, folks age 65-69, is where things are set to get tricky.

The Front Lines Of Trying Times

Immunize Colorado is a nonprofit organization working in cooperation with CDPHE to get vaccines into arms across all Denver communities.

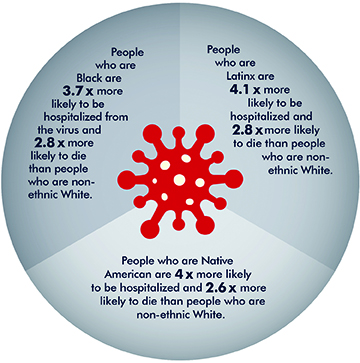

Stephanie Wasserman is the Executive Director of Immunize Colorado and has been out in the field and on the front lines since before the Covid-19 vaccine arrived. On a daily basis, she combats the social side effects of the pandemic. “My organization became gravely concerned because of the disproportionate impact Covid-19 has had on communities of color both in Colorado and nationally,” she begins. “We are not doing too bad in terms of getting shots into arms, but we are not meeting our equity goals. Also,” she continues, “there is significant hesitancy that exists in some communities due to the historic mistrust of the medical system.” Wasserman also cites “predatory behavior” as another driver of vaccine hesitancy, stating, “We have a very active anti-vaccine movement here in Colorado and they have recently targeted communities of color with disinformation.”

Clearly, this phenomenon reveals age-old fears that are easily agitated by misinformation. These negative (mostly online) messages tend to magnify the historical underservice of communities of color by the medical establishment and redirect that mistrust towards the vaccine rollout. Wasserman and her colleagues are undaunted and are fighting back via the recent launch of the Colorado Vaccine Equity Task Force (https://www.coloradovaccineequithe vaccines and y.org/). This site and its Spanish-translated partner site (https://www. equidadvacunacolorado.org/) are combatting the online misinformation with facts about the disproportionate impact COVID-19 has had while broadcasting endorsements from trusted, professional voices from communities of color as ambassadors for the vaccine. “The group comprises 35 members hailing from all walks of life,” Wasserman explains, “and all with one common trait — they identify as a person of color from an underserved community.” These include faith leaders, retirees, doctors, nurses, educators and one man who volunteered for one of the early Moderna clinical trials.

The Colorado Vaccine Equity Task Force is determined to vaccinate citizens in underserved communities.

In essence, the Task Force is mounting what is turning out to be a grassroots reeducation campaign to assuage fears, to combat misinformation and to ultimately get people from underserved communities vaccinated in order to stop the disease. “It has been super successful so far,” says Wasserman, “We’ve done policy and communication work, advocacy, outreach and engagement. It is really about getting into communities as much as possible, starting constructive conversations and allowing trusted community members to speak to their neighbors about the merits of the vaccine. “For example,” she begins, “We have two retired nurses on the Task Force who are very active and well known in their parish in the Montbello neighborhood. They held a pop-up clinic at their church and because it was hosted by them, hundreds of people signed up to be vaccinated and all supplies were gone in two hours.”

A Factually-Informed Outlook

Colorado State Representative Yadira Caraveo is also a Pediatrician with a medically-informed understanding of vaccines.

State Representative Yadira Caraveo, in addition to her role as an elected official, is also a pediatrician and a member of the aforementioned Colorado Vaccine Equity Task Force. Her primary roles are those of a coordinator and an administrator in the effort to achieve distribution equity of the vaccine. Regarding the timeline for getting the prescribed 70+% of the population vaccinated, Caraveo is hesitant to make an exact prediction. “I think the timeline has been changing as the realities on the federal level trickle down to the state level in addition to the lack of planning from the previous administration,” she explains. “Still, I think it is realistic and hopeful that we could get everyone who wants a vaccination taken care of by late summer, early fall.”

Optimism aside, Caraveo’s role in the Task Force has given her an informed perspective about vaccine hesitancy. “I think a lot of the uncertainty about this particular vaccine comes from the perceived speed with which it came out,” she begins. “People are out there saying ‘well, it can’t possibly be safe — it has only been 10 months since the pandemic started.’ But the important thing to remember is that science is ongoing and is built on decades of research and development. The research for these vaccines was built upon the research that was done for the MERS and SARS vaccines as well as mRNA that has been studied since the 1950s. It is a fact that scientists are continually working on things that they anticipate may be needed at some point — which is why this came out so quickly.”

Caraveo continues with a vaccine advocacy home-run hit, “As doctors, we’ve been talking for decades about how people don’t understand the need for vaccines because they haven’t seen a lot of the illnesses we vaccinate against now. Most people alive today have never seen someone with polio or tetanus because of the vaccines. This is the first instance in a century where we have developed a vaccine for something that people can see every single day — people who are getting sick and dying of COVID-19. The effects of the vaccine, or any vaccine for that matter are very minimal compared to what the illness does. The chances of anything happening [negatively] with the vaccine are one in a million as opposed to the chances of something bad happening should you get COVID-19.”

Caraveo ends with one last stark, unarguable, scientific gem of truth, “This is a perfect example of why vaccine hesitancy has grown over the last century and why it shouldn’t have grown. Now we can see, in real time, the effect of a vaccine versus the effect of an illness.”