“Justice is indispensably and universally necessary, and what is necessary must always be limited, uniform, and distinct.”

— Samuel Johnson

Immigration policy and enforcement in the United States is ensnared in a three-way collision between the inertia of the Legislative branch, the duty of the Judicial branch, and the will of the Executive branch. Plainly put, Congress writes the laws on immigration, the Department of Justice enforces those laws, and the President tells them how to do it.

This entanglement of the three branches of government — which were originally designed to be “separate and independent” — sits at the heart of the Immigration Courts’ struggle to efficiently apply due process and to fairly administer justice.

The Long Arm Of The Law

Many people attempting to immigrate to the United States do not have a concrete plan of how to proceed.

Meanwhile, a large contingency of professionals across the vocational spectrum are immersed in this deluge, attempting to navigate the confusion and find some currency of reason. These individuals include judges, lawyers, clerks, administrators, detention facility staff, Federal agents, law enforcement staff and many others.

Additionally, the people embroiled in the system who are experiencing the most uncertainty are immigrants (lawfully admitted foreign nationals), non-immigrants (lawfully but temporarily admitted foreign nationals), refugees, and asylum seekers. The latter two distinctions are people who are outside their home countries and unwilling to return due to persecution or a well-founded fear thereof. The common thread between all of these folks is they are trying to find a way to remain in the United States.

Whether the wishes of noncitizens are granted is determined by immigration policy, which is governed by the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). While this piece of legislation has been amended numerous times since its inception in 1952, Congress has demonstrated a profound inability to engineer the bipartisan cooperation necessary to make improvements which match the current demand.

Staggering Numbers

According to a June 12 article by Claire Moses of The New York Times, “The number of people crossing at the [southern] border is at the highest it’s been in at least two decades.” These individuals are arriving from places such as Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Peru, Haiti, and most recently, Ukraine. The vast majority are attempting to escape from poverty, authoritarian governments, natural disasters, gang violence, and war, while seeking economic opportunities.

A May 17, 2022, report issued by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) states that, during the previous month, U.S. Border Patrol agents recorded over 201,800 unique encounters at the southern border alone, along with 157,555 encounters nationwide in addition to 32,288 encounters by Office of Field Operations officers at various ports of entry. While some will be granted asylum, most will be detained and eventually removed (sent back to their home countries).

Unchecked and unbalanced, today’s Immigration policy hinders the courts therein from effectively handling the above numbers in anything resembling an efficient manner. The current system is fraught with hindrances of every sort, including a massive backlog of cases due to Covid-19 restrictions, staffing shortages, disruptive Executive branch policies, Congressional inaction, and political interference — to name a few.

An Immersed Perspective

The American Bar Association is proposing a set of solutions for streamlining the Immigration Court system.

While the immigration issue is a nationwide concern, a large number of cases are heard in Colorado in the Denver and Aurora Immigration Courts. Brian Clark is a Colorado attorney based in Alamo Placita, whose legal practice is focused on removal defense of noncitizens. Clark offers the unique perspective of a working professional who, on a daily basis, navigates and interprets the current set of policies for the intended benefit of his clients.

Clark offers detailed discourse on the obstacles faced by foreign nationals who are currently attempting to emigrate to the U.S. “ Under the current system there are short-term means that allow foreigners to come to the United States, such as tourist visas and student visas, but they’re intended to be temporary (although many people do overstay them),” he says. “Most foreigners attempting to emigrate to the U.S. in any long-term sense don’t really have a straightforward avenue for doing so unless they marry a U.S. citizen or can find a U.S. company to sponsor them as a skilled foreign worker.

“This, then, leaves the asylum process as a kind of default for many noncitizens who have left their countries of origin and have come to the United States, particularly for those from less developed countries. However, U.S. asylum law is very particular and tricky, with specific requirements that the person was persecuted in their country of origin based on certain immutable qualities about them (among other factors) — so a lot of noncitizens who come here for perfectly understandable reasons end up having a hard time showing that they qualify for asylum under the law. So, the primary obstacles faced by foreigners looking to immigrate to the United States are the lack of viable legal options available to them under current U.S. immigration law,” he explains.

Thank You, Mr. President

Clark faces myriad challenges as an Immigration Attorney, many of which stem from the tumult which arises every time a new President moves into the White House. “As a lawyer, when a prospective client comes to you seeking legal representation or counsel you have to assess the facts of their situation and candidly advise them of the viability of their case in light of the law,” he says. “That’s really tough to do when the interpretation, application, and enforcement of the law changes every time a new U.S. President is sworn into office, which is what has happened in recent years.

“A noncitizen who applied for asylum during the Obama administration may have had a strong case at the time the application was filed; and then after the interpretation of the law shifted during the Trump administration their case may have become markedly weaker as it moved through the Immigration Court process; but then during the Biden administration their asylum case may suddenly be revived and viable again. So, how strong a given case may be can depend on who the U.S. President happens to be when the case is presented in front of an Immigration Judge. That’s been one of the bigger challenges to practicing U.S. immigration law in the last few years — the unpredictability of the state of the actual law itself.”

Tumultuous Tides

Clark offers a front-row account of how the shifting balance of Executive power creates the see-saw effect which is so pervasive in today’s Immigration Courts. “In the last few years,” he begins, “The Department of Homeland Security has vigorously enforced certain aspects of immigration law under one administration, and then when the Presidency went to the other major party, they’ve been directed by the new administration to backtrack and dismiss the very same cases they were under orders to prosecute a couple of years ago. It’s anything but optimal, but immigration policy and enforcement have ping-ponged back and forth during the last three presidential administrations. And if the party in control of the White House changes again in the next election, then enforcement and application of the laws may well revert 180-degrees b

ack to what it was under the last administration, and all the cases that are being administratively closed and dismissed right now could be reopened again by the next administration.”

Not What It Seems

Among the frustrations of Attorney Clark, are the inaccurate generalizations by which the immigration issue is portrayed in mainstream culture. “I’m not a partisan idealogue,” he begins, “I got into immigration law in part because as a young person I lived abroad, and I fruitlessly tried to navigate another country’s immigration system without an attorney. In the current polarized American cultural climate, I find it tedious that immigration is such a hot-button issue that both major political parties tend to cast in sweeping hyperbolic binary terms. In reality, actually practicing immigration law is not about broad categories of ‘good guys’ versus ‘bad guys’ any more than any other part of the legal system is. It’s complicated and nuanced.

“Some noncitizens in the U.S. really, really get screwed over by the system and it’s deeply unfair and unjust how much the current structure of the law is stacked against them — but then there are other noncitizens who are appropriately removed from the country after they have had their day in court. That’s kind of how all aspects of the law are, in reality; individualized and particular to the people involved. Immigrants, as a group, are not a uniform cohort in almost any sense, so I find it irritating when moral grandstanding and fearmongering are done on behalf of, or against, ‘immigrants’ as though that term applies to a homogenous group of people. It does not,” he explains.

Hope On The Horizon?

Rather than concede to the idea that Immigration policy is destined to stay where it is, Clark offers poignant observations along with constructive ideas on how the ship could be righted. “The Immigration Court system is housed within the Justice Department,” he begins. “So, it is not really an independent court system like civil and criminal courts. That means that Immigration Judges are unfortunately deprived of full independence and autonomy, which can create problems when the Attorney General decides that an across-the-board change in the interpretation or application of the law is to be made. The current Immigration Court system is overwhelmed by a massive backlog of cases, which frustrates and exhausts everyone involved with it; the lawyers, the judges, the clerks and administrat

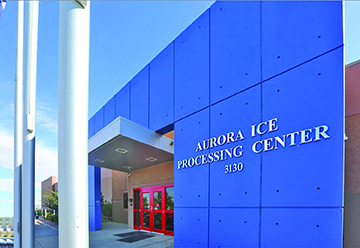

The ICE Detention Center in Aurora has a massive backlog of cases waiting to be heard due to Covid-19 setbacks.

ors, and the noncitizens whose cases it is supposed to adjudicate. The administrators of the Immigration Courts appear to be focused as of late on tackling the case backlog, which is certainly necessary in the short-term, but it’s not a permanent solution to the problems with the Immigration Courts.

“The most reasonable thing to do to fix the Immigration Courts at this point would be for Congress to pass reform legislation, and in so doing to follow the recommendations made repeatedly by the American Bar Association in the last few years — by making the Immigration Courts into proper independent Article III Courts rather than a part of the Department of Justice. Doing so would, at a minimum, help create more stability and consistency between different presidential administrations. Congress could also reform U.S. immigration law to allow for more temporary work options and other non-permanent avenues for otherwise law-abiding non-citizens to live and work in the United States lawfully. I won’t hold my breath though.”