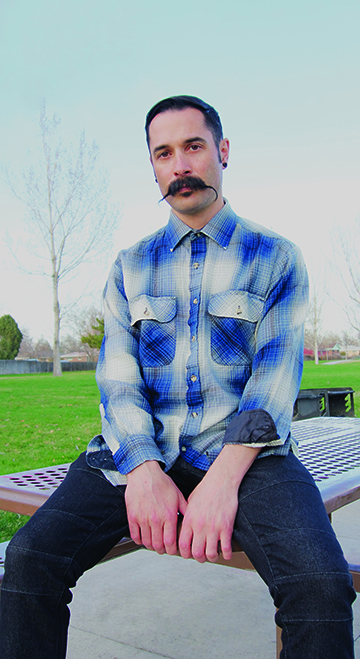

Morgan Sonsthagen

by Zilingo Nwuke

The year 2020 has brought a lot of misfortune to people all around the world, but John Larchick (JL) and his record label Time Stamp Records (TSR) have made good use of the time of solitude due to social distancing. Announcing the official start of the label on January 1, JL and his team have been busy in the lab making 2020 their year to emerge on the music scene with the release of their brand new music video and song Battle Royale.

“Battle Royale was an absolute gem to produce. I hate to say it, but my overgrown mustache may have taken the spotlight from even me on this one occasion. But honestly, from the beginning of the song’s inception, everything just started falling into place. From the creation of the beat and the vocal writing, down to the video concept and execution. It all just felt right. Those are the types of workflow that we as artists are searching for when we create,” stated JL, Owner and Producer of Time Stamp Records.

TSR, a childhood dream of JL’s, is a new indie record label out of Aurora/Metro Denver, Colorado. Time Stamp Records produces music and film. They also distribute and cultivate quality art, merchandise and music for film, radio, live events and television. And they have big plans for the future.

“Owning my own label has been a lifelong dream,” stated JL.

JL has been involved in the music industry from a very young age. At 17, he and his high school band, Reverend Orange Peel, sold out the Bluebird Theatre and earned the opportunity to play at the Ogden Theatre for New Year’s eve that same year. Both venues are icons in Denver. Ever since then he knew he had the knack for it and wanted a career in music.

“It wasn’t always glorious venues and big gigs though,” stated JL.

After high school, the band naturally dispersed to various colleges resulting in the dismantling of Reverend Orange Peel. “But I was still set on my musical quest. I was writing the music, learning to play instruments, and honing my craft virtually every waking moment. I started learning how to navigate all the facets of the ever-changing music industry. Everything from working with band members, writing songs, recording, booking, marketing to tours, videos, press releases, radio interviews and so much more.”

JL is no stranger to touring and has diligently booked gigs at countless venues across Colorado and surrounding states. “I’m super grateful for all of my past, present and future experiences, from the coffee shop gigs with no sound system to Boulder’s famous Fox Theatre. It’s my experiences as a musician and recording engineer that set me and this record label apart from others”.

JL has gone on numerous tours, occasionally accompanying some very notable artists. He has performed with acts such as Guru from Jazzmatazz, Fat Joe, Wu-Tang Clan, Ol Dirty Bastard, Pepper, the Pharcyde, Devin the Dude and others.

In addition, JL is the owner of a professional recording studio (Green Room Studios), the lead vocalist for JL Universe, a songwriter, multi-instrumentalist and a record producer. JL has released four albums and has helped a few fellow artists release albums of their own. His drive and motivation come from his love for music and the desire to create amazing art. He wants to encompass everything in the industry and assist other aspiring artists to reach their goals. Cultivating Time Stamp Records into a renowned success for all the artists signed under the label is where his sights are now set.

“Running this label, to me, it’s a really big responsibility and it’s a big honor. To be able to provide a service and to be able to put out people’s truths,” said JL. “Music and art are so personal and there are so many really dope artists that don’t get a chance to have a sounding board, to have somebody there to ricochet ideas and concepts, and grow a plan. That is what I am focused on when we sign artists. We are helping the artists generate their vision and then really feed that vision so it can grow and blossom into something bigger.”

JL is drawn to music that resonates with him, as opposed to claiming loyalty to a specific genre of music. He listens to and supports everything from electronic to funk to hip-hop to country. He has a hard time fitting Time Stamp Records into a specific category because he works with artists from across the board. When considering an artist for the label, JL really focuses on the quality of character and integrity presented in their work. He values artists with great work ethic, clarity, and dedication to their craft. He values artists with ambition and a drive to create something amazing for the world. Because of his familiarity with the industry, JL has a keen eye for the foundation required to establish a successful musical career.

“My goal is to become the record label that I always needed as an artist. To create a space and platform for artists and projects to fully develop. I have built, and I am still building, the frameworks and no one style or artist’s journey will be the same, but the process to get to our goals are similar,” said JL. “TSR is here to assist in that self-discovery and execution of plans. My dream is to make art that transforms time and space and that stamps the moment we are living in through expression and human connection. The end goal is to make creations that resonate, fulfill dreams and win Grammys.”

Sometimes all an artist needs is someone to give them a little nudge or to point them in the right direction for success. They can be filled with talent and musical genius, while struggling with the skill of getting noticed and releasing their art. They need a mentor or a leader. And that is precisely what JL and Time Stamp Records is. TSR is paving the way for musicians. He guides them on the path toward achievement. That way, everyone wins. In November, TSR plans to announce a statewide contest which is calling on artists to submit their work for the chance to win a single produced and released by TSR along with other great prizes.

Time Stamp Record’s song and video, Battle Royale was quickly followed by JL’s second single release of 2020, The Other Side. The single is paired with a creative and thought-provoking video and the song is seeing great success in just the first few days of release. In addition, JL Universe has several queued singles ready for release later this year and into 2021.

To listen to JL’s work and to follow JL Universe, Time Stamp Records or Green Room Studios (Colorado), search and find them on Facebook and Instagram. You can also find JL Universe’s video and single — Battle Royale on all digital streaming platforms like Spotify, Apple Music and Youtube.

Time Stamp Records’ long anticipated website has been revamped and reintroduced in an easy to use and enlightening format. Plus, the brand-new winter line of TSR merchandise will be available in November and contains fabulous new clothing styles.

For more news and exclusive music, art and culture, follow TSR on all social media platforms and sign up on the mailing list at www.timestamprecords.com. New artists, new songs, new videos, new merch, new inspirations and new beginnings are all happening, right now, at Time Stamp Records.