by Robert Davis and Luke Schmaltz

Under the current Denver Zoning Code 11.12.2.1.B.2 (DZC), the number of people who can live together as a household (who are not related by blood) is limited to just two. While this does not include blood relatives or persons under 18, it places tangible parameters on what is commonly known as a “single-family home.”

After a series of public hearings about how to best accommodate growth in Denver over the next 20 years, residents in several neighborhoods are voicing their displeasure with City Council’s proposal to update its residential use rules in order to increase density in neighborhoods.

A Civic Dilemma

As the housing crunch continues to tighten, community leaders and other influencers are looking for ways to address the needs of vulnerable populations who face difficulty finding viable housing but does not cost the city any government money. These include persons at risk of becoming homeless, college students, people overcoming addiction and special needs individuals who must reside near service facilities — among others.

The Group Living Project (a City of Denver initiative) seeks to update the DZC’s definition of “household” and regulatory policies which would extend from single family homes to assisted living facilities, shelters and group homes. This initiative aims to amend the current Group Living Code to “increase flexibility and housing options for residents, to streamline permitting processes for providers while fostering good relationships with neighbors, and to make it easier for those experiencing homelessness, trying to get sober or who have other special needs [to] access services with dignity.”

Proponents argue that the plan would allow Denver to address its affordability problem by building non-traditional housing. Critics say that while the city does have an affordability problem, fixing it should not come at the expense of current homeowners.

This policy proposal is a key element of Blueprint Denver 2019, a 300-page document that outlines the city’s plans to accommodate growth through 2040. While it is not regulatory in nature, the hefty document serves as a supplement to a similar plan passed in 2002 and is meant to guide local government decision making into the future.

A Significant Change

The proposed amendment would increase the number of unrelated adults who can live together from two to eight in a property of up to 1,600 square feet in size. The provision would also allow another adult for every additional 200 square feet of finished floor area in larger properties. The breadth of proposed revisions to the DZC include more conservative recommendations of just four to six unrelated adults per property, yet all proponents of the amendment are championing the impending positive impact.

If the above parameters of eight adults in one home were amended into law, the new “household” definition would be applicable to 42% of single and two-unit properties. Similarly, nearly 58% of detached residences and duplexes could house up to nine unrelated adults and approximately 41% could house 11 or more adults unrelated by blood. While the new parameters would mildly affect “household” living in single-unit and multi-unit properties, they would greatly expand the potential for group living facilities — the number of which could rapidly increase — seemingly overnight. These could include properties that, after a quick remodel, could be repurposed into homeless

shelters, community corrections facilities (halfway houses), special care facilities, transitional housing, assisted living, nursing and hospice, co-ops, sober living, elderly care and student housing.

Questionable Motives

The Group Living Code Amendment is being proposed and supported by the Group Living Advisory Committee (GLAC). An insider of the group (wishing to remain unnamed) recently divulged that, curiously, over 75% of members and stakeholders in the GLAC have ties to for-profit group living businesses and organizations. Aside from household living, the above list of group living distinctions does one thing: it opens residential districts to dynamic, overlapping sectors of highly lucrative commerce. While increasing the number of people landlords can legally charge rent to, the amendments could potentially make Denver a prime target for corporate investors and foreign interests. The changes could cause yet another spike in residential property values, but then, as the rooming houses fill up, values could quickly decline due to lack of parking, noise, overcrowding, safety issues and sanitation concerns.

In recent years, measures similar to what the GLAC is proposing for Denver have been passed in Seattle, Atlanta, and Chicago. While Seattle’s housing crunch is well documented, perhaps it is not common knowledge that many homes in the city were bought by investors who divided up living rooms and garages to turn multi-bedroom homes into dormitory-like dwellings for up to 12 renters. In Atlanta, the loose definition of “household” is being exploited by outside and foreign investors who are turning neighborhoods into districts full of by-the-room renters with little stability and no protections. These units go for an average of $140 per week in properties with scant common areas and in many cases — one bathroom for the entire domicile. Meanwhile, a similar trend in Chicago dubbed “upzoning” has rendered an opposite effect city planners hoped it would have. In January of last year, Citylab .com reported: “A new study of zoning changes in Chicago finds that they led to higher, not lower, local home prices, while having no discernible impact on local housing supply.”

Follow The Money

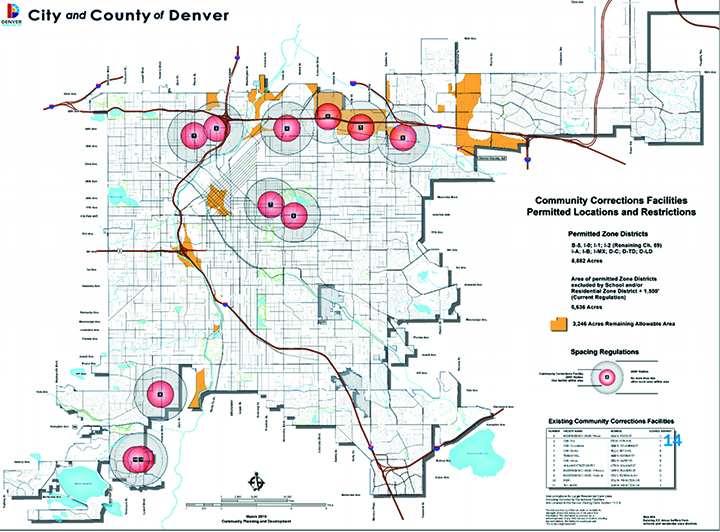

Critics of GLAC assert that the GLAC’s plan was conceived via tunnel vision, because it contains various glaring instances of considerable oversight. The critics point out that the amendment includes no measures ensuring that new facilities are evenly spread throughout the city. It does not limit the opening of more facilities in communities that already have a concentration of such. It includes no stipulations for specific distances between facilities and it does not restrict for-profit homes in neighborhoods where no demand exists. For opponents, the bottom line remains that rental income on a single- family household unit could go from charging one family, to collecting week-to-week and month-to-month rent from eight to 12 residents. That’s a hefty incentive for landlords and investors in for-profit group living organizations.

“I just don’t see any positive things about it whatsoever,” said longtime Denver resident Jerry Doerksen. “There are already several houses in our area where four or more unrelated individuals are living together and the appearance of the home and yard reflects the lack of personal interest,” Doerksen said. “Four inhabitants, four cars. There is no enforcement of current code regulations, and it seems improbable that there would be any enforcement of regulations under the proposed plan.”

“Denver is a diverse city and the planners should take account of all the different characteristics of each neighborhood and the wishes of the residents,” one Washington Park resident who wished to remain anonymous told the Glendale Cherry Creek Chronicle in an emailed statement. “Further, Denver needs to assess all related impacts of such zoning changes.”

While Denver’s affordability issues live on, some homeowners see themselves as stuck in a no-win situation. They’re going to be forced to give up ownership of their property or their stake in a neighborhood, or both.

“Yes, there is a problem with the high cost of housing in Denver but it’s certainly not fair or appropriate to place the solution of the problem on the backs of homeowners who have chosen to live where they do in order to avert the very situations this proposal would create,” said Doerksen.

Whether the proposed amendment to the DZC will work is still a matter of speculation. At best, it could offer relief to the lack of affordable housing and at worst, it could convince reasonable people to not want to live In Denver at all. Either way, the GLAC is pushing to make group living property investors a lot of money.