“The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” English proverb

On a typical day, Dwayne Peterson awakens at 4 a.m. to go to the gym. Until recently, he would begin his day at the Colorado Village Collective (CVC)-run housing facility known as Beloved Community Village (BVC) in Denver’s Globeville neighborhood. On his way out of the gated “tiny home” enclosure, he would regularly witness other residents getting high on illicit substances, engaging in the trade of illegal drugs, and selling packages of dope through the chain-link fence. “I chose to get up early and leave the premises for the day to minimize the amount of interaction I would have with other residents,” he explains.

Peterson is a longtime Colorado resident who attended CU Boulder for undergraduate and postgraduate studies. He is a professional ballet dance instructor, teaching students of all ages and ability levels through his company, This is Dance, LLC. Four years ago, his landlord of 17 years sold the house where he was renting an apartment. The property was quickly slated to be demolished — leaving Peterson and four other residents suddenly unhoused.

An Unwelcome Guest

Dwayne Peterson encountered racism, violence, a death threat, and other adverse conditions at the CVC’s Beloved Community Village. Image courtesy of Dwayne Peterson

Peterson is sober with no criminal record and has never been a drug user — nor has he ever been diagnosed for mental health conditions. These factors not only made him an outcast among the BVC residents, but also made him the target of stalking, death threats, and racial attacks — which ultimately forced him to move out for the sake of self-preservation. “I was in an altercation the first day I moved in,” he begins. “There are constant disputes among residents because of the drug economy and the problems which inevitably arise” he explains.

At weekly BVC resident meetings, “there were heated disputes and physical altercations,” Peterson says. While he was quick to voice his concerns about the nonstop illegal activity, the resident-on-resident fighting, the all-night noise, and the open use of drugs — his protests fell on deaf ears as he was ignored by administrators and harassed by fellow residents. He could not shake the feeling of being constantly scrutinized by his neighbors as a non-drug user. Essentially, he was seen and treated as a rat.

Looks Great On Paper

CVC is headed by Cole Chandler, an ordained minister with a Master of Divinity (M.Div.) degree from Baylor University. He runs a non-governmental organization on a mission to “bridge the gap between the streets and stable housing by creating and operating transformational housing communities in partnership with people experiencing homelessness.” The CVC website further states, “We embody radical solutions to homelessness: housing that centers human dignity, empowerment of marginalized voices, and design solutions that are affordable, sustainable, and community oriented.” While the part about “radical solutions to homelessness” is definitely true, the rest — according to Dwayne Peterson’s eyewitness accounts — is window dressing at best.

Not What It Seems

Peterson firmly states, “Cole Chandler is lying to you. Plain and simple. The BVC is just a haven for criminal activity — a sanctuary for people to openly engage in crime — a contamination of resources and the community as a whole.” Peterson repeatedly went through the established CVC protocol for filing complaints about other residents who were making meth on site, preparing other drugs such as cocaine and heroin for distribution, and selling them directly from the property. “There was trafficking between residents and outsiders,” he says. “Exchanges were taking place right through the fence. People would drive up, make the trade and the customer would either drive off or just sit there and get high in their car before leaving.”

Blatant Disregard

When Peterson would file a complaint through the on-site “complaint portal” he would then receive notice that the situation was being investigated. “What would happen,” he states, “is that an administrator would knock on the resident’s door and casually tell them there was a complaint against them without having a discussion or conducting an investigation of the premises in question.” Essentially, the offending party was given ample time to cover their tracks, remove evidence, and come up with an excuse as to why they were being accused of drug trafficking, assault, etc. Peterson maintains, “These were haphazard investigations with unsubstantiated conclusions.”

Another instance of negligence on the part of CVC/ BVC staff occurred late one night when an outsider climbed over the fence and jumped into the enclosure to pursue a resident. An altercation ensued followed by a fight and the intruder stabbed the resident. “There was blood all over one of the decks,” Peterson explains. “Then, staffers started cleaning up the crime scene without even calling the police. The Tiny Home Village Director, Dorothy Leyba, was on site and said to a protesting Peterson, ‘We will handle this internally.’”

Rampant Racism

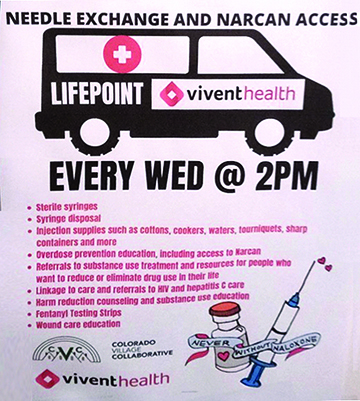

The CVC hosts Lifepoint Needle Exchange so their SOS residents can have plenty of fresh supplies for shooting up illicit, highly addictive drugs. Image courtesy of: Dawn McNulty

In an open letter to law enforcement and all others who should be concerned with his plight, Peterson describes a racially hostile environment where Caucasian residents repeatedly harass, threaten, and use racial slurs against African-American residents like himself. “I know of two previous individuals of color who resided at Beloved “Community” Village [who] left not because they located housing but attributed their weariness to being violated by Caucasian individuals residing at this emergency homeless shelter,” he writes. In the same letter, he elaborates further, “A current individual of color residing at this emergency homeless shelter, who continues to be violated by Caucasian individuals residing at Beloved “Community” Village and their guests, is reticent to communicate their being harassed. This individual believes [that by] reporting their being violated that they will be evicted.”

During the two years he lived at BVC, Peterson’s vigilance placed him in the crosshairs of one particularly aggressive Caucasian resident. “This person called me ‘a f***ing n***er’ and threatened to kill me by shooting me with a gun,” he explains. In the aforementioned letter, Peterson states, “I report these crimes to the city of Denver, law enforcement, and Denver City Council. Beloved “Community” Village staff, Cole Chandler, and Colorado Village Collaborative, et al have not performed their due diligence investigating these crimes. In ignoring the individuals committing these crimes, Colorado Village Collaborative, et al has only emboldened these individuals to continue their nefarious and insidious activities and lifestyles. Cole Chandler, regardless of the funding Colorado Village Collaborative, et al is receiving, is lying to the public and those he engages for funding.”

At The Crossroads

Peterson estimates that during the time he resided at BVC, he made at least 50 complaints with the Denver Police Department. “Nothing was ever done,” he explains. “That’s why I started blanketing Denver with what’s going on in BVC.” Drawing on his postgraduate-level college education, the well-spoken Peterson has drafted and sent articulate letters explaining the conditions, the lawlessness, and his specific circumstances to news outlets, lawmakers, government officials, law enforcement, and more. Peterson has recently been featured in articles by The Denver Post, Westword, and other publications. “Before I left,” he says, “They [CVC staff] became more aggressive towards me. They don’t want me talking to the Denver City Council or the press.”

At the time of this interview, 02/04/2022, Dwayne Peterson had been out of the BVC/CVC system for just two days — speaking from the parking lot of a Denver motel. His frustration is palpable, as he weighs his options for the foreseeable future. The irony of his situation is truly baffling, as a plethora of local agencies such as Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, St. Francis Center, and many others have refused to give him assistance because he is “high functioning” and “low risk.” “I was told by Colorado Coalition for the Homeless that I can’t be helped because I don’t have any problems,” he says.

To compound matters, Peterson has been diagnosed with cancer and is wary of overnight shelters. “They are unsanitary and unhygienic (think Hepatitis A, B, and C). Homeless shelters, in general, invite disease and violence,” he states. Additionally, and it should go without saying — the Covid-19 pandemic has made it difficult, and at times impossible, for Peterson to run his business which is built on in-person learning.

Reach Out

In yet another effort to remedy his situation, Peterson has started a GoFundMe campaign to raise funds so that he can secure long-term housing without having to endure the deplorable conditions in places like CVC’s properties and overnight shelters. Concerned readers who are interested in helping Mr. Peterson can donate here: https://www.gofundme.com/f/seeking-to-secure-housing.

Proliferation Of Dysfunction

Across town, the battle for the sanctity of the Lincoln/La Alma neighborhood continues, as Dawn McNulty — a resident of the adjacent Baker neighborhood — continues to fight the CVC’s recent installment of a Safe Outdoor Space (SOS) at 780 Elati St., on the outskirts of the Denver Health and Medical Center campus. Among her many concerns is the glaring reality that this property is governed by the same policies as the CVC’s other villages — including the BVC — former home of Dwayne Peterson. The fact that the Lincoln/La Alma SOS is within 1000 feet of three Denver Public School properties is in itself cause for alarm. “This is a bipartisan issue with well-intentioned, compassionate people working on both sides,” McNulty explains. “We must demand more of our city’s officials to ensure public health and safety. SOS sites are an incubator for crime and disease.”

Citizens for a Safe and Clean Denver do not want addicts and people with mental illness living next to schools and families with children. Image courtesy of Terry Hildebrandt, PhD

McNulty and fellow citizens of a group known as Citizens for a Safe and Clean Denver are staunchly against Safe Outdoor Spaces. They intend to address and remove the glaring oversights and extreme safety hazards to neighborhoods populated by families with children. As it turns out, their fight just got a whole lot tougher, as Denver City Council recently voted to allot $3.9 million of Denver taxpayer money to Cole Chandler and CVC so that they can install more city-sanction drug camps. If you think this issue doesn’t affect you, think again. An encampment of mentally ill, drug-addicted, illness enabled people could be coming to your zip code very soon. These folks do not stay in the camp all day, so they will most certainly be dropping by for a sprawl and an afternoon dope fix on your front lawn. Welcome to the new Dystopian Denver.

Adding insult to injury, the CVC enables the use and injection of illegal drugs by allowing Lifepoint/Vivent Health to distribute — for free — supplies such as syringes, needles, tourniquets, cotton swabs, cookers, and sharps containers to residents of Safe Outdoor Spaces. Also, should their assisted addiction service prove to be too effective, they supply Narcan for overdosing addicts and Fentanyl testing strips for suspicious-looking illegal narcotics that are well known among users to be deadly. Saintly enablement indeed.

Your Tax Dollars Not At Work

Meanwhile, Dwayne Peterson’s parting statements are stark, harrowing, and ring as true as the pavement under his feet. “Homelessness is being managed, not rectified. What astounds me is that no matter how much money is being thrown at it, it keeps getting worse.”