by Mark Smiley | Apr 23, 2021 | Main Articles

Criminal And Civil Failure To Report Gifts Added To Sexual Assault And Harassment Claims

by Glen Richardson

Worries Mount: Denver School Board Director Tay Anderson’s legal problems are growing. Two progressive organizations he has been a part of (Black Lives Matter 5280 and Never Again, Colorado) have accused him of either sexual assaulting or sexually harassing female members. Now the nonpartisan Campaign Integrity Watchdog has filed civil and criminal complaints concerning tens of thousands of gifts he has alleged to have solicited.

Tay Anderson, the highly controversial 22-year-old Denver School Board member’s legal problems are escalating at a dizzying pace. He is now facing new criminal misdemeanor allegations relating to his failure to file required reports on his repeated solicitation for gifts related to myriad events including claimed medical expenses, a trip to Washington, D.C., and a baby gift registry.

Tay Anderson, the highly controversial 22-year-old Denver School Board member’s legal problems are escalating at a dizzying pace. He is now facing new criminal misdemeanor allegations relating to his failure to file required reports on his repeated solicitation for gifts related to myriad events including claimed medical expenses, a trip to Washington, D.C., and a baby gift registry.

Sex Assault And Harassment

He was previously accused of sexually assaulting an unnamed woman by Black Lives Matter 5280 (“BLM”) which he denied and claimed he needed more information. BLM demanded that Anderson issue a public apology and seek assistance from a licensed professional with relevant expertise before he was welcomed at the group’s meetings or events. The group later stated that more women had come forward.

Anderson then acknowledged a May 2018 Denver Public Schools investigation found that he had engaged in retaliation while advocating on behalf of former Manual High School Principal Nick Dawkins, whom the district had investigated following employee complaints of harassment and bias.

Anderson then acknowledged a May 2018 Denver Public Schools investigation found that he had engaged in retaliation while advocating on behalf of former Manual High School Principal Nick Dawkins, whom the district had investigated following employee complaints of harassment and bias.

The six female members of a gun reform organization, Never Again Colorado, which Anderson served as president in 2018, issued a statement that Anderson created a hostile work environment making them feel unsafe by, inter alia, “talking in code about female board members in front of them (with romantic/sexual subtexts), daring female board members to perform sexualized actions, having conversations comparing the attractiveness of female board members, and making lewd comments in private to female board members.” The women were underage at the time of the incidents.

This time Anderson apologized and stated he would now “plan to engage and consult with restorative and transformative justice professionals.”

Anderson declared that he welcomed any investigation of his conduct. On April 6, 2021, he got his wish when the Denver Public Schools Board of Directors announced that it had secured an agreement with the Investigative Law Group to investigate the claims of women that he had assaulted and harassed them.

Anderson alienated many of his white female supporters in Central Park (formerly Stapleton) and elsewhere when he tweeted out “My brother really picked out a white woman with pumpkin pie over me for thanksgiving. This is another level of hurt.” The outrage over the implied racism caused him to delete the tweet.

Cornucopia Of Gifts For Anderson

Campaign Integrity Watchdog, LLC, a non-partisan organization dedicated to campaign integrity and transparency of public officials filed an Economic Crime Complaint with the Denver District Attorney’s Office alleging criminal misdemeanors by Anderson for failure to report numerous fundraising solicitation schemes including:

Campaign Integrity Watchdog, LLC, a non-partisan organization dedicated to campaign integrity and transparency of public officials filed an Economic Crime Complaint with the Denver District Attorney’s Office alleging criminal misdemeanors by Anderson for failure to report numerous fundraising solicitation schemes including:

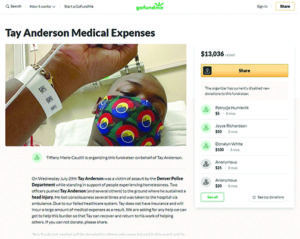

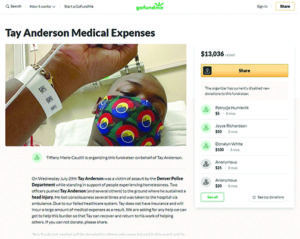

- Anderson claimed unspecified medical expenses alleging that on July 29, 2020, he “was a victim of assault by the Denver Police Department while standing in support of people experiencing homelessness” and hit his head. His campaign manager created a Go Fund Me page in which he received over $13,000 in gifts. He was required to report all gifts above $65 but failed to do so according to the Complaint.

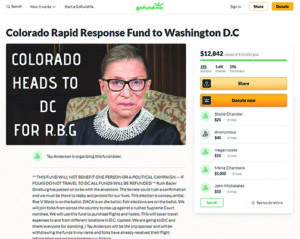

- Anderson personally created a Go Fund Me page on September 19, 2020, to pay for his and others trip to Washington, D.C., for the funeral of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg and raised almost $13,000 and the Complaint indicates he again failed to report the same.

Gifts Galore: Campaign Integrity Watchdog has filed civil and criminal complaints against Tay Anderson for his failure to disclose tens of thousands of dollars of unreported gifts.

It also appears that Anderson began soliciting gifts in late 2020, of up to $1,000 on the Target website for a child he was expecting. There appear to be only 11 gifts he registered for that have not been purchased for him at press time. Anderson has had an interesting relationship with Target. He had tweeted that he and family members had been racially harassed at an unspecified Target location. Then on November 30, 2020, he tweeted that he had collapsed from severe chest pains while shopping with his family at Target. His failure to report the Target Baby Registry gifts would appear to potentially violate C.R.S. Sec. 24-6-203.

Anderson would not be subject to jail time under the statute but could be punished by a fine of up to $1,000 for each violation and the Complaint alleges multiple violations. Campaign Integrity Watchdog also filed a Complaint with the Colorado Secretary of State alleging campaign and political finance violations of C.R.S. Sec. 24-6-203, based on the same set of facts. The Secretary of State, Jena Griswold, could impose her own fines under Colorado law.

Anderson would not be subject to jail time under the statute but could be punished by a fine of up to $1,000 for each violation and the Complaint alleges multiple violations. Campaign Integrity Watchdog also filed a Complaint with the Colorado Secretary of State alleging campaign and political finance violations of C.R.S. Sec. 24-6-203, based on the same set of facts. The Secretary of State, Jena Griswold, could impose her own fines under Colorado law.

Campaign Integrity Watchdog officer, Matt Arnold, stated that “public officials who deliberately evade the legal disclosure requirements for financial activity betray the public trust. Elected officials — and those seeking to obtain or retain elected office — cannot be above the law. Such ‘official’ violators must be held accountable to the law, so that ‘some animals — are not more equal than others’.”

Campaign Integrity Watchdog officer, Matt Arnold, stated that “public officials who deliberately evade the legal disclosure requirements for financial activity betray the public trust. Elected officials — and those seeking to obtain or retain elected office — cannot be above the law. Such ‘official’ violators must be held accountable to the law, so that ‘some animals — are not more equal than others’.”

Controversial Glendale Meeting

Tay Anderson became well known to Glendale residents when in July of last year, he appeared at a City Council meeting with State Representative Emily Sirota to protest Glendale agreeing with Governor Polis on masks while opting out of Tri-County Health Department’s requirements. He managed to alienate many at the meeting by verbally mocking and denigrating anyone who spoke with a position contrary to his own.

Anderson did not respond to requests for comment on the latest charges against him.

by Regan Bervar | Mar 19, 2021 | Main Articles

“This is the power of gathering: it inspires us, delightfully, to be more hopeful, more joyful, more thoughtful … more alive.” – Alice Waters

by Luke Schmaltz

by Luke Schmaltz

It is with hopeful trepidation that most Denverites look to the summer months. Yet, while the vaccine rollout is having a diminishing effect on the pandemic, it may still be too soon to dig the picnic basket out of the attic. Regardless, Denver offers a dizzying array of festivals, fairs and outdoor events every year. Sadly, as most residents know all too well, most of them had to be skipped in 2020. With any luck, circumstances just might improve to where the simple joy of gathering with friends to enjoy the warm weather, great food and diverse entertainment the Mile High City’s legendary events have to offer.

“Pandemic fatigue” is one of the softer terms folks are using to call what most honest people are describing with more vivid language such as extreme shut-in fever, Covid-19 craziness, or isolation delirium. While reaching herd immunity through vaccination is a process that disrupts nature in a good way, social distancing is fairly unnatural for most, and could be blamed for the all-too ubiquitous modality of depression and malaise among the populace.

Taste Of Colorado

Taste: Taste of Colorado draws hordes of hungry visitors to downtown Denver every year.

Originally dubbed the Festival of Mountain and Plain, this gathering was established in 1895, and revived in 1983 by the Downtown Denver Partnership. Every year, restaurateurs, foodies, chefs, sauciers, pastry cooks and gustatory retail vendors of every stripe gather to market their businesses, showcase their talents and sell their treasures. The event happens every Labor Day weekend and is tentatively scheduled for September 4, 5 and 6, 2021. Britt Diehl, Senior Manager of Public Policy & Special Projects at DPP, explains, “… unfortunately we don’t have anything to report at this moment — we are looking at options based on public health guidelines/outlooks.”

CHUN People’s Fair

Every summer, the Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods Association (CHUN) throws a party in Denver’s Civic Center Park that offers something for anyone and everyone. This celebration of music, creativity and diversity welcomes artists, performers and spectators from every background imaginable in a two-day event that features music on over half a dozen stages. Typically held over the first weekend of June, the Fair was canceled in 2019 amid rumors of declining revenues and in 2020 for obvious reasons. Whether it is set for a resurgence in 2021 remains to be seen.

Cherry Creek Arts Festival

Arts Festival: The Cherry Creek Arts Festival hosts artists of every sort from around the world.

This event is perhaps the most approachable of all the offerings in an otherwise upscale, exclusive district. 2021 marks the 30th anniversary of this celebration of “Artivity” otherwise known as “Art for Everyone.” The event features “visual and performing arts and educational and immersive art experiences” and attracts upwards of 350,000 visitors along with 260 local and regional artists and hosts. The date for 2021 is yet to be set in stone, but if it takes place, it will most likely do so over the Fourth of July weekend — Friday, Saturday and Sunday, July 2, 3 and 4.

First Fridays

Denver art lovers have a total of six art walks to choose from on the first Friday of every month. These varied and diverse offerings take place across an array of vastly different districts and offer the city’s finest in galleries, museums and studios. These art walks take place in the River North Arts District, the Art District of Santa Fe, Golden Triangle Museum District, Tennyson Street Cultural District, South Pearl Street and 40 West Arts District and Block 7 Galleries. The latter is the most family-friendly of the lot, featuring a variety of dining options, a movie theater and a wintertime ice rink. Visitors to the previous five gatherings can expect to encounter a diverse offering of food trucks, restaurants, bars and breweries. Face masks are currently required by most establishments.

Cinco de Mayo

Cinco de Mayo: Cinco de Mayo is a beloved cultural tradition that will be celebrated regardless of an event being scheduled for downtown Denver.

This festival commemorating the victory of the outnumbered Mexican Army over French forces during the 1862 Franco-Mexican War takes place on or around the 5th of May. This year, that date falls on a Wednesday, so the tentative Civic Center Park celebration will take place on the weekend prior — depending on what event planners decide in what will most likely be an 11th-hour verdict. The two-day event attracts over 400,000 visitors and is particularly well known for offering an incredible array of Colorado Mexican cuisine and hosting events such as the Green Chili Bowl Cook-Off, a taco eating contest, a lowrider car show, and the infamous Chihuahua races.

The Colorado Dragon Boat Festival

Dragon Boat: The Colorado Dragon Boat Festival lights up Sloan’s Lake Park and has a definite date set for September 2021.

This unique gathering describes its mission as “the premier organization celebrating and promoting the culture, contributions and accomplishments of Colorado’s Asian-American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities.” Thankfully, this year’s event has a set date for September 25 and 26, in Denver’s Sloan’s Lake Park. Historically, the festival has taken place in July, but for 2021 event planners are no doubt hedging their bets on the theory that the pandemic curve will most likely flatten by fall rather than summer. Visitors can expect an otherworldly immersion in arts, entertainment, cuisine and of course — dragon boat races.

Large gatherings which are sanctioned and approved by the powers that be will return eventually, here’s to hoping it is sooner than later.

by Mark Smiley | Mar 19, 2021 | Main Articles

Wash Park Home Built In The 1890s Faces Wrecking Ball; ‘Park Won’t Be The Same If Home Is Razed,’ Residents Stress

by Glen Richardson

Stunning Site: Home, sweet historic home’s prominent location creates an established and familiar feature for both Wash Park and the Mile High City.

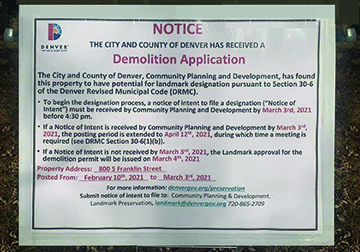

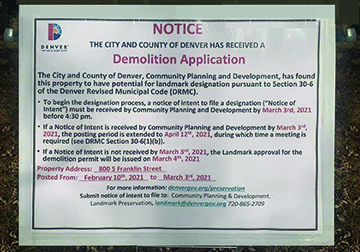

In a neighborhood where real estate is in high demand, demolition threatens a rare Wash Park Queen Anne home built no later than 1890. Neighbors were surprised and shocked when a demolition notice was posted at the 800 S. Franklin St. home by the City & County of Denver.

The oldest occupiable property from the 19th Century remaining in the neighborhood, it is located on a large corner lot across Franklin St. from Wash Park and across E. Ohio Ave. from St. John’s Church. The home is a rare remaining example of the Queen Anne Style in West Washington Park.

Representing the distinctive visible characteristics of a Queen Anne, it has the asymmetrical massing including projecting octagonal bays, steep gabled roofs, deep classical eaves and hooded windows. The porch features Tuscan order columns and classical entablature — an architectural section located above the columns on the building’s exterior. Largely developed  in the period between the world wars, many of the houses in the neighborhood were constructed in more revivalist or eclectic styles such as Tudor revival or Craftsman.

in the period between the world wars, many of the houses in the neighborhood were constructed in more revivalist or eclectic styles such as Tudor revival or Craftsman.

Saving Historic Site

Ironically the bid to bulldoze the $2,300,000 home was posted in March as Historic Denver began celebrating five-decades of saving and highlighting historic treasures under threat of annihilation. The non-profit got started by saving the Molly Brown House from demolition in 1970. The organization is hosting a 50th bash at the Molly Brown House Museum now through Sept. 19. The celebration includes a “50 Actions for 50 Places” campaign for sites worthy of preservation action.

Sixth generation Coloradan Drew Carder — who has spent nearly his entire life in Wash Park — is among the neighborhood admirers and supports nominating the Franklin St. home as a community mecca worthy of preservation protection. He says he doesn’t know much about the home other than it is one of the last remaining pieces of the neighborhood’s history. “I feel like this community should be given more of a chance to respond.”

Like Carder, Justin Moorland has spent most of his life in or around Wash Park. Today he lives on the 600 block of S. Gilpin, one block away from the Franklin St. house. “It has always been my favorite home at the park. I find it unique because of its obvious age, modesty and setting. It is truly from another era.” Admits Liz Schanker, “I guess that proximity gives me extra incentive to save the home.” She lives right next door to 800 S. Franklin and says she has lived in Wash Park long enough to be able to imagine the structure that would go up on the site and doesn’t want that to happen. “There is a plethora of new, urban mansions in the neighborhood but only one white farmhouse that predates the park.”

Stunning Setting

Stunning Site: Home, sweet historic home’s prominent location creates an established and familiar feature for both Wash Park and the Mile High City.

Set far back from Franklin St., the home has an unusually large front yard at the corner of E. Ohio. Because of the house’s large, open lot and prominent location, it creates an established and familiar feature for both Wash Park and the Mile High City. One of the neighborhood’s first buildings, it was constructed before the City of Denver became the City and County of Denver. Moreover, despite its age the house retains a high degree of integrity.

The original Queen Anne structure has experienced some alterations including the stuccoing of the masonry, the northern addition plus alterations to some window openings. Nonetheless, it still retains integrity of design, materials and workmanship to communicate its Queen Anne style. The home is in its original locations, and while the area around the house has been altered over time, the house retains its setting through its relationship to Washington Park and Smith Lake. The interior includes a breakfast nook, vaulted ceilings, walk-in closets and fireplace. The structure is encircled by a wrap-around front porch.

Bid To Bulldoze

Wash Park developer-builder Aaron Grant is the person seeking demolition of the historic home. He is owner-managing-broker of South Gaylord St.-based Grant Real Estate Co. Retailers and residents will recall it was his firm that bulldozed long-standing stores along Denver’s second oldest commercial block to build Park Coworking. The company website claims, “We maintain history and character in the Wash Park neighborhood through real estate design and development.”

In conversations with relatives of the owner who sold the house to Grant Real Estate, neighbors were purportedly told that Grant articulated to them “what they wanted to hear as a seller.”

Treasure Threatened: Demolition threatens this rare Queen Ann home located across Franklin St. from Wash Park. The oldest occupiable property from the 19th Century remaining in the neighborhood, the house has retained a high degree of integrity despite its age.

At the time he was purchasing the property, Grant also allegedly indicated that he wanted to keep the shell of the home and remodel the interior. “We know now this was probably never his intent,” they say.

Noteworthy Owners

According to the Denver Assessor’s records, 800 S. Franklin St. was constructed in 1890. If the date is accurate, it would make the house one of the earliest remaining buildings in the West Wash Park neighborhood. Additionally, it confirms the house was built prior to the City of Denver becoming the City and County of Denver, which was not until 1902.

The earliest record of home ownership was by lumber tycoon Joseph Sterling who started Sterling Lumber & Investment Co. Records suggest, however, the house may be older that 1890 as a 1900 fire destroyed building records prior to 1890. The last prominent person to live in the Franklin home was William H. Burnett, a distinguished jurist who served on the Denver County Court for 17 years.

In 1964 Burnett served as President of the Judicial Research Foundation and became head of the American Bar Association’s Section of Judicial Administration. The judge lived at the Franklin St. address with his wife Margaret from 1963 until his death in 1973. He was at the height of his career when he lived at the address, therefore the property bears a strong association with him and his significance as a local judge and reformer.

by Regan Bervar | Mar 19, 2021 | Main Articles

“Humans are startlingly bad at detecting fraud Even when we’re on the lookout for signs of deception, studies show, our accuracy is hardly better than chance.” – Maria Konnikova

by Luke Schmaltz

by Luke Schmaltz

Over the last year, the pandemic has proven that there is no level of trickery that is too low for some people.

Humanity’s ever-industrious scammer contingent will seemingly stop at nothing to achieve its prime objective — to separate you from your money. The current populace of frightened, poorly informed, emotionally vulnerable people has created a lush marketplace for fraud. Folks who desperately want to stop isolating, masking and disinfecting their lives away and get back to living them instead are falling victim to COVID-19 vaccine scams.

These ploys are disguised as websites, emails, phone calls, text messages and — yes — personal visits to your home. The perpetrators make an offer, convince victims to provide personal information or money and then they disappear. Here are some of the scams currently underway and how to spot them.

Free Vaccines: The vaccines from Johnson & Johnson, Moderna and other companies should be free, no exceptions. Image: Johnson & JohnsonFree Vaccines: The vaccines from Johnson & Johnson, Moderna and other companies should be free, no exceptions. Image: Johnson & Johnson

All Vaccines Should Be Free

Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer and their emerging vaccine-making counterparts are being compensated by the U.S. Government. There should be no cost to you other than a small administration fee, if any. If someone approaches you via phone call, text message, email, or in-person visit with an offer to “sell” you a dose or a vial of vaccine, report them to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) at ReportFraud.ftc.gov. Sinovac is a China-based company which has tested a successful vaccine, yet this is not approved for distribution in the United States. Regardless, several social media campaigns were running ads claiming to be making this vaccine available for American consumers — for a price.

Scammers Have Bad Grammar

Anyone with a computer, an internet connection and a few basic skills can make websites and send emails. Since most of the vaccine scams are purported by criminals who are overseas, their lack of skill with the English language will be apparent in the text of the email or website landing page. In the case of an email, look for basic mistakes in punctuation, pluralization, spelling and euphemistic language. Also, no signature on an email is a red flag as is any email that appears to be from a government agency, pharmaceutical company, or a vaccine distributor. Websites offering vaccines will be using a specific set of keywords in their titles to attract traffic. Be on the lookout for terms such as “private vaccine, testing update, COVID validator, cure COVID, testing update, Corona vaccine and COVID -19.”

Phishy Phone Calls

Phone Scams: Phone calls from scammers are the main way scammers separate people from their money.

Stateside scammers or those with a believable command over American English may call you out of the blue. They will claim to be working in some sort of an official capacity, either for a pharmaceutical company, a healthcare provider, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) or some branch of the U.S. Government. The next giveaway is that they will ask you to “verify” your identity by providing them with some sort of personal information whether it is your Medicaid policy number, your birth date or your SSN. Some of them may go so far as to tell you they are going to show up and personally administer the vaccine for you. Remember this: whether on the phone or via email, verifiers are liars.

Bad Business

BBB: The Denver Better Business Bureau is keeping tabs on local and international scammers via their Scam Tracker Tool.

Meanwhile, the Denver chapter of the Better Business Bureau is keeping tabs on these scammers. Content and PR Specialist Keylen Villagrana offers insight into an array of both international and locally-run

scams. “Fake unemployment claims, stimulus check scams, puppy scams ([they] are rising as more people are working from home) and employment scams for work-from-home positions. [There is] even an elaborate romance scam operating overseas where victims are turned into ‘money mules’ in order for scammers to retrieve fake unemployment claim money. They use victims for their U.S. based bank account and ask them to wire money to a bank account [that is] very likely overseas. (Wire transfers can’t be traced),” she says. Of all the current ruses, one is unanimously more popular than the others. Villagrana explains, “Consumers are contacted after they have received the COVID-19 vaccine (although many are contacted that haven’t even received the vaccine), to take a survey and in exchange for a ‘gift.’ All they have to do is pay for shipping and handling ranging from $2.99-$19.99 depending on

the gift they choose. Most never receive anything and some have reported unauthorized charges.” Folks are in luck, however, as this agency keeps a running tally on all past and current scams via their “Scam Tracker” tool available here: www. bbb.org/scamtracker.

Trash Can Treasure

Ads such as the one mentioned above claiming to be selling vaccines should be disregarded. The messaging features such as Facebook Messenger are also avenues scammers will take to try and get your attention through personal messages containing “incredible” deals on Covid-19 vaccines. The main rule of thumb here: if it sounds too good to be true, it’s a scam.

Legitimate Source: Immunize Colorado is one of the legitimate sources of “real” vaccinations.

Some Lines Can’t Be Skipped

Yet another scenario involves scammers who claim to be able to do the legwork for you and “track down” your vaccination. Others offer a similar service by promising that they can use their contacts in the medical industry to help you “skip the line” and get a vaccination sooner than the current tiered rollout system allows. These are scams that will require the service fee be paid in advance and once the money is sent, that’s all she wrote.

Thankfully, legitimate sources are standing by to provide citizens with answers about the specific tiers of the vaccine rollout and where the efforts are on the projected timeline. You can find out more by going to Colorado Vaccine Equity www.colorado vaccineequity.org, Immunize Colorado www. immunizecolorado.org and the Colorado Department of Health and Environment covid19.colorado.gov.

by Mark Smiley | Feb 19, 2021 | Main Articles

Glimmer Of Hope As My Fair Lady Is Set For August Opening; Renovated Clocktower Cabaret, Cleo Parker Dance Already Open

by Glen Richardson

Red Rocks Recovery: Opening of the 4,000-person Red Rocks Amphitheatre when the weather warms up would be a sure sign Denver’s urban heart is pumping again. AEG Presents has yet to signal it is booking summer concerts.

From restaurants to retail the Cherry Creek Valley is slowly reopening for business. But Denver’s urban heart — live concerts, theatre, comedy and the creative arts — remain mostly shut down creating an economic calamity that has drained the cultural lifeblood of the city.

Up until now the city’s pace-setting institutions — the Denver Center for Performing Arts (DCPA), Red Rocks Amphitheatre and the Colorado Convention Center — have been dark since the pandemic hit. So have a half dozen other theaters plus key dance, music and performance spaces. Reopening has proved far more daunting than anyone could have imagined.

Statewide mass Covid-19 vaccinations efforts plus restrictions lowered to Level Yellow in 33 counties, including Denver, have reignited hope and anticipation that venues and productions will begin reopening this summer. The opening light switch, in fact, has already been flipped at several spots and entertainment insider chatter suggests that opening could be imminent at additional venues by summer-fall.

Glimmer Of Hope

Against All Odds: The Denver Center for Performing Arts is tentatively planning to present Broadway’s touring version of My Fair Lady in the Buell Theatre Aug. 11-22. All of DCPA’s venues have been closed since the pandemic hit.

With summer solstice just 112 days subsequently to March 1, there are signs that the cloud of Covid-19 is starting to lift and the city’s cultural scene will reignite.

The Denver Center for the Performing Arts has announced that Saturday Night Alive will return June 12. The 40-year-old fundraiser has been reconceived in order to follow public gathering restrictions. “Currently, we hope to welcome both a virtual audience as well as on-site guests,” explains DCPA President-CEO Janice Sinden. “We envision an evening that can accommodate a smaller, in-person gathering and leverage the HD broadcast capabilities of the Seawell Ballroom.”

Furthermore, DCPA is tentatively planning to present Broadway’s touring version of My Fair Lady in the Buell Theatre Aug. 11-22. From the Lincoln Center Theater, the New York Times says revival of the musical “reminds you how indispensable great theatre can be.”

Small Venue Test

Convention Comeback: Meetings, tradeshows at the Colorado Convention Center aren’t likely in large number until the second half of the year. Booked through 2023, the city seeks to hang onto the business.

On its 15th anniversary The Clocktower Cabaret under the historic D&F Clocktower on the 16th Street Mall launched live shows beginning Valentine’s Day. Additional shows are expected this month in the nonprofit company’s 240-seat theater following months of renovation.

Cleo Parker Robinson Dance has also reopened her 240-seat theater in the former church site at 119 Park Ave. West. Official opening followed frenzied work to renovate the 24,000-sq.-ft. complex. Up to 20 area performing arts companies that have survived the pandemic are lined up to rent the space. Included are spin-off dance companies Moraporvida Dance, Nu-World Contemporary Dance Theatre and Feel The Movement.

Larimer Lounge is testing the waters with a Denver-via-Ecuador pop artist Neoma concert on July 10 followed by rock combo Matt Rouch & The Noise Upstairs the next day. Then on July 24 indie folk duo Shovelin Stone is scheduled to perform. The Larimer Lounge’s sister club, Globe Hall, is serving a barbecue dinner and a show and if all goes well, that venue will begin hosting shows of its own. While the Larimer Lounge experiments with dinner service, restaurants are reversing the test by trying out concerts to build business during the pandemic. Lost City Café in River North, for instance, plans to kick off a summer-long benefit series on its patio.

Ratings, Tech & Cash

Dancing Into Renovated Digs: Cleo Parker Robinson Dance has also reopened its 240-seat theater on Park Ave. West. Up to 20 area performing art companies that have survived the pandemic are lined up to use the space.

Official ratings, technology and money are also key factors playing into the comeback of concerts and events. If, for example, the state moved the pandemic dial to Blue, DCPA would be able to entertain 175 guests in the newly-renovated Wolf Theatre. Moreover, fundraisers and weddings could host up to 175 guests in the Seawell Ballroom.

The pandemic has triggered technology while also altering event formats. After going digital last year, City Park Jazz is bringing back the free live concert, but with a mix of both virtual and live programming.

With a $2 million anonymous gift, the Colorado Symphony is now able to pay its employees through this summer. Moreover, Conductor Christopher Dragon’s contract was renewed through the 2022-24 season. Likely, it will also mean Boettcher Concert Hall will have additional live concerts plus the return of Symphony concerts to Red Rocks.

Sway Of Promoters

Recapturing Denver’s pre-pandemic momentum will require the booking of touring entertainers, shows and events by Denver’s two major event promoters AEG Presents and Live Nation. Founded by Philip Anschutz, AEG is the exclusive ticket seller for all Denver venues including Red Rocks. Summer shows here remain iffy despite the warmup including those booked by AEG at the Bluebird, Ogden and Gothic Theatres.

The odds aren’t much better at the Marquis Theatre or Summit and Fillmore Auditoriums that Live Nation books. Variety, however, did report Live Nation was “confident live music would return this summer.”

Financially it normally doesn’t make sense for national touring musicals or shows to visit Denver if they can’t also perform elsewhere around the country. Bottom Line: Shows and entertainers coming to Denver earlier than this fall (2021) will likely be one-offs, series from a single artist at a single venue, or regional tours playing unconventional venues.

Bedeviled Path Back

Fundraiser First: The showcase of live theatre has announced that the 40-year-old fundraiser Saturday Night Alive is returning June 12. Event will feature both on-site guests and a virtual audience.

The trajectory of infections, vaccinations and “overall behavior” will determine the number and size of this year’s summer-fall openings. The fear, of course, is that it only takes one super-spreader event to ruin it for everyone. Just as Denver seemed like it was finally in a place where people could plant a flag on the ground and claim a fresh start, trouble erupted.

After reopening three weeks earlier, the 40,000-sq.-ft. Grizzly Rose — known for hosting country music and featuring a 2,500-sq.-ft. dance floor — was caught by TV and social media cameras packed with hundreds of people inside the dance hall without masks when only 50 people were permissible.

Owner Scott Durland quickly closed the venue just north of Denver off I-25 voluntarily. Just two days later, however, Tri-County Health ordered the site shut down until further notice. The club had been cited for the same violations last fall.

by Ashe in America | Feb 19, 2021 | Main Articles

by Robert Davis

They’re Back: Jason Lewiston, whose Green Flats project was defeated in 2018, is back proposing a project called The Holly Street Townhomes. Also pictured is Anna DeWitt, who owns one of the homes being sold to make way for the new development.

A proposed development on S. Holly Street in Denver’s Hilltop neighborhood is reviving old baggage between neighbors who don’t want change and a developer with leverage to muscle.

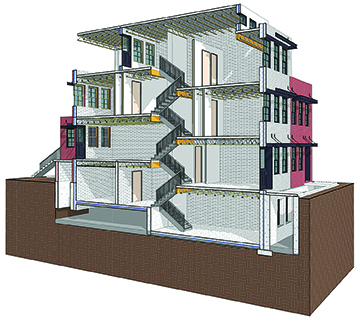

Known as The Holly Street Townhomes, the project will combine five parcels between 219 and 227 S. Holly to create a multi-family, co-living complex. Each of the six townhomes contains four individual units which are sold as “shares” of the group home. The units are priced at $150,000 for about 600 sq. ft. for a bedroom, kitchenette, bathroom, and sitting area.

Florence Sebern, who lives in the neighborhood, said the Townhomes are eerily familiar to the Green Flats project her neighbors defeated in 2018. Through an intricate petitioning process, residents were able to force City Council to require a supermajority of 10 votes to pass the necessary rezoning request.

After only eight Council members voted for the project, developer Jason Lewiston told Denverite the setback was a “metaphor for the future of Denver. Are we going to retain whites-only, single-family zoning … or are we going to get past race-based zoning from the 1960s?”

Now that Lewiston is back, this time on the heels of a controversial overhaul to the city’s zoning code, some residents are feeling blackballed by their elected officials.

“Some people in Denver have a particular disdain for Hilltop residents as white, privileged, and somehow willing to surrender to whatever a developer wants to build,” Sebern told the Glendale Cherry Creek Chronicle in an interview.

Sebern also described the timing of Lewiston’s re-appearance in the neighborhood as “curious.”

Destined For Scraping: These townhomes on South Holly Street in the Hilltop neighborhood would be leveled to make way for a multi-family, co-living complex.

Lewiston formed a co-living agency called The Co-Own Company in June 2020 while the Denver housing market was resting. Research by the National Association of Realtors found the Denver metro area experienced a one-year price growth of one percent over that summer.

Even though the Townhomes currently do not hold a building permit with the city, the units are already listed on the MLS. And since the project could not have been built in Hilltop before the Group Living Amendment passed, Sebern concluded the development plan had to be submitted with some foreknowledge that the amendment would pass.

Sarah Wells, Co-Own’s director of sales, was a voting member of the Group Living Advisory Committee (GLAC) while Gosia Kung, an architect, sits on the Denver Planning Board.

Members of both groups are appointed by the Mayor. GLAC disbanded after the amendment passed and members of the Planning Board are appointed for three-year terms on a volunteer basis. All Planning Board members hold outside employment with other firms, corporations, and nonprofit organizations.

Meanwhile, Denver’s form-based zoning code is designed to create predictable outcomes for developers. All zoning permits must be shown to be consistent with a previously approved Large Development Framework, Infrastructure Master Plan, General Development Plan, Regulating Plan, or Site Development Plan. Furthermore, it cannot “substantially or permanently injure the appropriate use of adjacent conforming properties.”

Inexpensive Homes: The Holly Street Townhome units are priced at $150,000 for about 600 sq. ft. for a bedroom, kitchenette, bathroom, and sitting area.

But, Wells said the neighborhood wasn’t chosen to stir up trouble. Instead, Co-Own wanted to bring the project to Hilltop because of its proximity to downtown, its parks, restaurants, and shops.

“Additionally, the lot we’ve chosen already houses a multi-unit building so it allows us to create a new complex that is similar, will have the same number of units and will blend in well with the surrounding area. The architectural style we’re using is intended to complement established neighborhoods and provide a beautiful place for people to live affordably and earn an ownership stake,” she added in an email.

Hilltop is one of Denver’s most expensive neighborhoods with an average home value north of $1 million, according to Zillow. The proposed Townhomes will sell for a combined $600,000 in total, nearly double what Lewiston was asking for in Green Flats.

Overall, the Townhomes will attract more density to the neighborhood as well. Green Flats was designed to offer affordable options for the families and teachers of nearby Carson Elementary or Hill Middle School. The Townhomes will consume more land which may leave less room for off-street parking.

For teachers like Anna DeWitt, who owns one of the homes being sold for the development and teaches French at North High School, the Townhomes represent a chance for Denver to begin embracing its future.

“The Townhomes offer millennials and middle class workers a chance to build equity through a new type of living,” she told the Chronicle. “This can help a lot of people get out of living paycheck to paycheck. What’s wrong with that?”

Tay Anderson, the highly controversial 22-year-old Denver School Board member’s legal problems are escalating at a dizzying pace. He is now facing new criminal misdemeanor allegations relating to his failure to file required reports on his repeated solicitation for gifts related to myriad events including claimed medical expenses, a trip to Washington, D.C., and a baby gift registry.

Tay Anderson, the highly controversial 22-year-old Denver School Board member’s legal problems are escalating at a dizzying pace. He is now facing new criminal misdemeanor allegations relating to his failure to file required reports on his repeated solicitation for gifts related to myriad events including claimed medical expenses, a trip to Washington, D.C., and a baby gift registry. Anderson then acknowledged a May 2018 Denver Public Schools investigation found that he had engaged in retaliation while advocating on behalf of former Manual High School Principal Nick Dawkins, whom the district had investigated following employee complaints of harassment and bias.

Anderson then acknowledged a May 2018 Denver Public Schools investigation found that he had engaged in retaliation while advocating on behalf of former Manual High School Principal Nick Dawkins, whom the district had investigated following employee complaints of harassment and bias. Campaign Integrity Watchdog, LLC, a non-partisan organization dedicated to campaign integrity and transparency of public officials filed an Economic Crime Complaint with the Denver District Attorney’s Office alleging criminal misdemeanors by Anderson for failure to report numerous fundraising solicitation schemes including:

Campaign Integrity Watchdog, LLC, a non-partisan organization dedicated to campaign integrity and transparency of public officials filed an Economic Crime Complaint with the Denver District Attorney’s Office alleging criminal misdemeanors by Anderson for failure to report numerous fundraising solicitation schemes including:

Anderson would not be subject to jail time under the statute but could be punished by a fine of up to $1,000 for each violation and the Complaint alleges multiple violations. Campaign Integrity Watchdog also filed a Complaint with the Colorado Secretary of State alleging campaign and political finance violations of C.R.S. Sec. 24-6-203, based on the same set of facts. The Secretary of State, Jena Griswold, could impose her own fines under Colorado law.

Anderson would not be subject to jail time under the statute but could be punished by a fine of up to $1,000 for each violation and the Complaint alleges multiple violations. Campaign Integrity Watchdog also filed a Complaint with the Colorado Secretary of State alleging campaign and political finance violations of C.R.S. Sec. 24-6-203, based on the same set of facts. The Secretary of State, Jena Griswold, could impose her own fines under Colorado law. Campaign Integrity Watchdog officer, Matt Arnold, stated that “public officials who deliberately evade the legal disclosure requirements for financial activity betray the public trust. Elected officials — and those seeking to obtain or retain elected office — cannot be above the law. Such ‘official’ violators must be held accountable to the law, so that ‘some animals — are not more equal than others’.”

Campaign Integrity Watchdog officer, Matt Arnold, stated that “public officials who deliberately evade the legal disclosure requirements for financial activity betray the public trust. Elected officials — and those seeking to obtain or retain elected office — cannot be above the law. Such ‘official’ violators must be held accountable to the law, so that ‘some animals — are not more equal than others’.”